Ball Joints

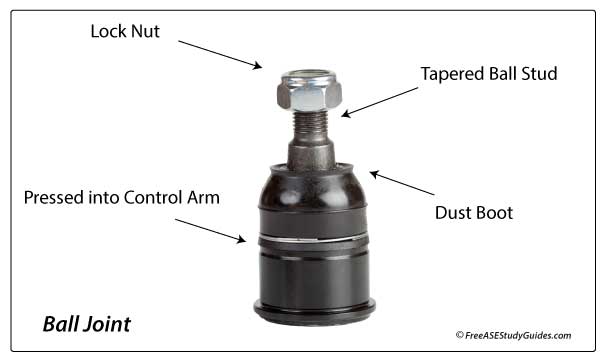

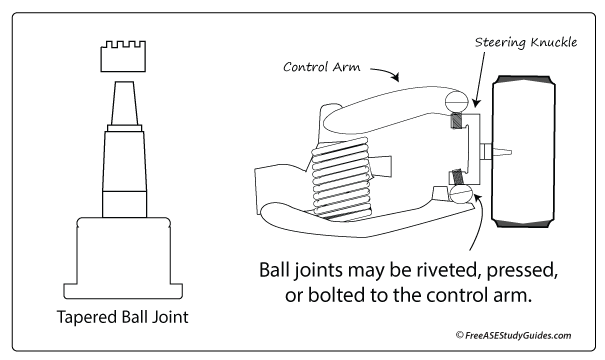

Ball joints allow the steering knuckle to swivel as the vehicle turns. They also provide for up and down movement as the vehicle brakes and travels over bumps in the road. The ball stud and socket provide a smooth swivel for the steering knuckle. They're preloaded and have a tight fit as they rotate on a thin layer of lubricant, similar to a person's shoulder socket. A rubber wedge or a spring keeps the ball stud tight in its seat. As they wear, clearance increases, and noise and vibration occur.

Conventional systems found on older passenger cars and many of today's light trucks have two ball joints: a load-bearing ball joint and a follower ball joint. The load-bearing joint is attached to the control arm that seats the suspension coil spring. They tend to wear sooner and cause a clunking or popping sound when excessive clearance develops between the ball and socket.

Most of today's passenger cars are front-wheel-drive models with struts. These systems contain only one follower ball joint. Vehicle weight rests on the upper strut mount instead of a load-bearing ball joint.

Many replacement ball joints have a zerk grease fitting and need lubrication after installation. Others are sealed and contain sufficient lubricant from the manufacturer to last the lifespan of the ball joint. Some ball joints contain a wear indicator; when the grease fitting becomes flush or recesses into the base, replace the ball joint. Others require a jack to unload the joint to measure end play.

If the spring is between the lower control arm and the frame, place the jack under the lower control arm close to the ball joint. Place the jack under the vehicle's frame if the spring is between the frame and the upper control arm. Raising the wheel off the ground unloads the ball joint.